Tony Byrd was growing increasingly discontented with his job running the coffee shop in the lobby of IBM’s main building in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. He had been working there since he graduated from high school nearly a decade ago, and with two young kids to provide for at home, Byrd, 27, was itching for a new start.

Now you can find him buying coffee from the same bar he used to run, except this time as a full-time IBM employee.

Byrd’s transition from barista to IT worker is part of what has become increasingly necessary in today’s technology industry: companies looking to nontraditional places to fill a growing talent gap.

Byrd is a recent graduate of IBM’s apprenticeship program — a 12-month-long training program for workers without advanced degrees, where he learned coding languages like JavaScript, Python and C#. It’s a win-win for Byrd and IBM. He has the chance to start a career in the tech industry and receive a big raise from his barista days. And IBM has gained an employee who says he’s in no hurry to leave Big Blue.

“It meant a lot and took a weight off my shoulders,” Byrd said of being hired full time. When asked whether it made him feel a sense of loyalty to the company, he said it did.

IBM’s apprenticeship program was pioneered at its RTP office in 2017. Since then, the program has spread to several IBM offices. In two years, it has led to nearly 200 employees being taught how to code, run cybersecurity and a host of other skills. Around 90% of people in the program have become full-time IBM employees, the company said.

Kelli Jordan, director of career and skills at IBM, said the program was born of necessity, with hundreds of thousands of IT job openings around the country going unfilled.

“Every company is becoming a tech company in some sort of way. … It is a bit of a numbers game,” she said. “There’s over 700,000 (unfilled) tech jobs, and when you look at candidates that are coming out of the traditional pipeline, there are only about 70,000 with a computer science degree. Those numbers don’t match up.”

So IBM came to the realization it had to recruit differently.

“That meant looking at community colleges and coding boot camps,” she said, rather than just depending on the universities producing enough computer science graduates.

The apprenticeship model — where potential workers get paid while they learn new skills — has been around for a long time, mainly in the trades. IBM says it’s one of the first tech companies to try the model. In the IBM program, apprentices receive 200 hours of learning on average, both in the classroom and in real-life projects, applying new skills and getting real-time feedback.

Jordan said she has received loads of calls from other companies about how to set up a similar program.

Advertising

IBM isn’t the only local tech company looking for ways to recruit employees from nontraditional places. And with more than 28,000 IT job postings in North Carolina in December — a 10.8% increase from the year prior, according to the N.C. Tech Association — there are plenty of options for the most qualified workers, forcing companies to focus on retention and mining new talent.

A survey of Raleigh-area chief information officers by the recruitment firm Robert Half found that 46% of them were willing to be more flexible on skills requirements and provide training to new hires.

Companies like Lenovo have created internship pipelines at local community colleges, giving opportunities to dozens of students every year. Fidelity is now funding a scholarship at Wake Technical Community College for students studying cloud storage and cybersecurity to chip away at the local talent gap in those fields. In the past year, SAS Institute has made it easier for autistic workers to find opportunities at its company. And Credit Suisse has launched an initiative at its RTP office to help train workers — many of them women — who have been out of the workforce for an extended period of time.

“It was created to target an overlooked talent pool of qualified candidates,” Sophia Wajnert, head of Credit Suisse Raleigh, said of the program in an interview with The News & Observer last year. “We realized there were talented individuals who struggle to return to work after a career break.”

As an added benefit, tech companies could also increase their workforce diversity by hiring from nontraditional sources of talent. North Carolina, as a state, lags behind much of the country when it comes to diversity in the tech industry, despite it being one of the more diverse states.

“For us, it definitely has helped with diversity,” IBM’s Jordan said. “We do see candidates who may have not been able to go to a traditional college but have been able to build skills.”

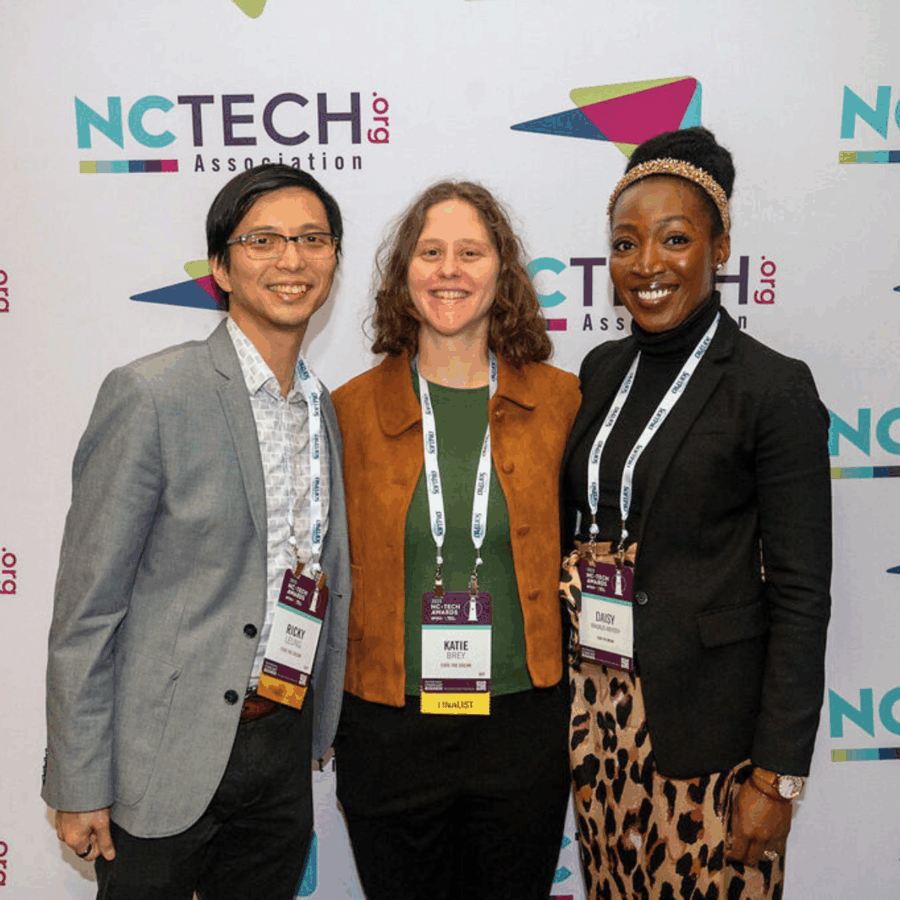

Dan Rearick, executive director of Code the Dream, a nonprofit that focuses on teaching immigrant youths how to code, said his coding boot camp was founded on the premise that tech companies would be willing to hire workers without bachelor’s degrees. A lot of the organization’s students did well in school, he said, but because they were Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA, or “Dreamers”) many skipped college because they didn’t qualify for in-state tuition.

“Employers are, for the most part, very willing to consider people who don’t have a traditional background, or a computer science degree,” Rearick said. But he has found that most need to land a long-term internship at a company before they will be hired.

Fernando Osorto, 25, who immigrated to North Carolina from Honduras, worked in carpentry before he enrolled at Code the Dream, learning coding languages like Ruby on Rails. He now works at Duke University as a web application developer.

In his view, more companies should take a chance on coding boot camp graduates because they spend as much time learning code as many students in traditional schools. Yet, when he was applying for jobs after graduating, he thinks his resume was often passed over because he didn’t have a four-year degree.

It wasn’t until he proved his capabilities in an internship at Duke that he got a full-time gig.

“A lot of the jobs I applied to in their qualifications they would say you need a bachelor’s in computer science,” he said. “So even though I had the experience … . I think that was the reason I didn’t get a call back.”

If more companies looked beyond people with four-year computer science degrees, Osorto said, “I think it would greatly impact the outcome of the diversity in the tech world.”