I’ve never known a place quite like the Episcopal Farmworker Ministry. Since the 1980s they’ve served thousands of migrant farmworkers from their outpost in Dunn, North Carolina, tending to the needs of the invisible and poorly paid workforce on which our agricultural economy depends. In the summer of 2018, the Ministry went into high gear like never before, providing emergency food, clothing, and supplies following the double-punch of Hurricanes Florence and Michael. I was one of many volunteers who pitched in to help.

One evening I helped Juan Carabaña, the Ministry’s tireless outreach coordinator, load a van full of groceries before heading out to two camps. With the fall sweet potato harvest curtailed due to devastating rains, the workers there hadn’t been paid in weeks and were running low on food. The camps were two that hadn’t been visited in a while so we couldn’t be sure our printed directions were accurate. They weren’t. After wandering for more than hour to find the first camp, and another hour to find the second, this career software developer had an idea: there needs to be an app for this.

“We need a map on our phones showing us exactly where the camps are. Plus, accurate descriptions of camps, and notes from previous outreach visits. And photos would be awesome.” Lariza Garzon, the Ministry’s new Executive Director, described over coffee what she’d like to see in a farmworker outreach app. I got to work.

There are thought to be more than two thousand migrant farmworker camps in North Carolina – nobody can say for sure. Some consist of old bunkhouses tucked into the woods, some are small trailer parks, and some are old farmhouses. Some are surrounded by barbed wire fences or lack indoor plumbing. None is the kind of place you or I would want to spend the night, much less live for several months. But they are all filled with people with the same basic needs as you and me, things like food to eat and clothes to wear. And those are the kind of needs that workers and volunteers at the Episcopal Farmworker Ministry cater to when they go on outreach.

My app was ready a few weeks after my coffee with Lariza. Or so I thought. The tryout was a complete disaster: the user interface was difficult to navigate, almost none of the camp information was right, and the app crashed so often it was useless. I spent that evening scribbling furiously from the passenger seat, logging our camp visits into a spiral notebook instead of the app. I had put too many features into that first version and hadn’t taken enough time for testing and debugging.

The next version had just the camp map and nothing else, so on the next outreach visit it did a bit of good. Juan could at least tap a button to launch GPS directions without manually typing a street address. I still logged into my notebook, recording how many workers we met with and what we delivered to each camp, and took a few photos of each camp. The next day I transferred everything from my notebook into the app’s database, uploaded the photos, and added another user feature to the app. This process repeated itself every week. Slowly but surely, the app got better and the Ministry’s database of outreach information and photos grew.

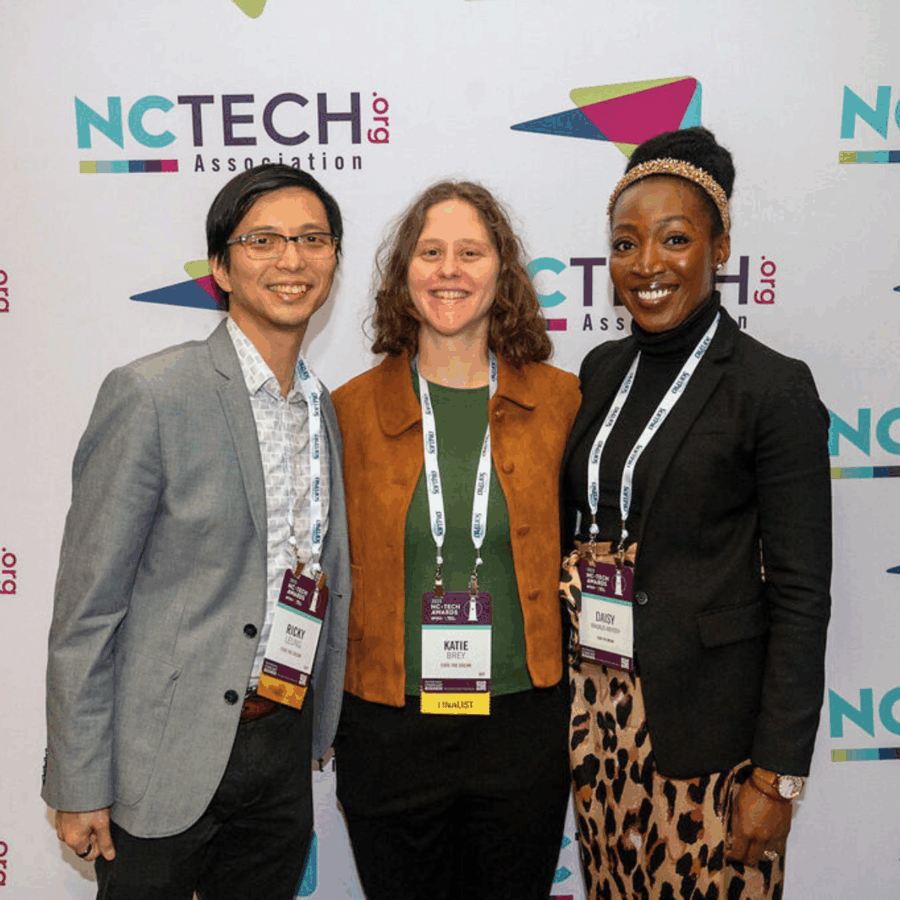

In April I teamed up with Code the Dream, a remarkable non-profit software development organization that offers free training to people from low-income communities. One of their developers, in fact, grew up in a farmworker camp herself. Over the summer, she and her colleagues turned my prototype app into a real app, complete with security, performance, and stability features. They went with Juan and me on outreach, came up with features I hadn’t thought of, and also gave the app a name: Vamos.

As the agricultural season drew to a close, Vamos had recorded outreach visits to more than 80 camps. On the last scheduled outreach, the app was used for everything: to select camps to visit, to navigate to each, to log how many farmworkers were visited and what was provided, and to take photos. Nobody had to scribble furiously from the passenger seat or remember to file an outreach report later.

As I write this in December 2019, the camps are empty but Vamos is not. It is filled with data and photos from this year’s outreach. Next spring, when outreach workers head out to a camp, they’ll call it up on the app, tap the directions button and just start driving. With Vamos, they can spend their time providing services instead of knocking on doors and wandering dirt roads looking for camps. There’s still work to be done on the app, to help make outreach even more productive, and there are many more camps to add to the database. But there is an app.

This blog post originally appeared on the Episcopal Farm Worker Ministry’s website. To learn more about EFWM’s work, click here.